Commissions just don’t come out of the blue.

My honest opinion: those popular “selling” artists in gallery settings have their work impersonally offered without real knowledge of the client who’s buying what they created. The transaction becomes a commercial arrangement more or less. A better description for my type of client is “Patron.” My patrons are rarely strangers. They are people I know or have met: friends and friends of friends.

I was contacted by a Marina owner and player on my son Lindy’s local hockey league team. He had seen one of my seascapes a friend had purchased from me, liked the style and had a specific subject he wanted for his wall. This is how most of my direct commissions come about.

Dan is in the boat world. Yacht sales are what he does. Boats of all types surround the marina — in the water, trailered, and up on blocks. Dan’s office is located down the beach road in a town called Sea Bright, in the midst of boats moving constantly around his expansive yard. His favorite yacht design comes out of Rockland, Maine: a “down east” vessel manufacturer known as Back Cove.

When we shook hands in his office I knew I’d seen him at the rink once or twice with Lindy, providing a familiarity that doesn’t require a whole lot of preliminaries.

Dan got right to it.

“I want a Back Cove 41, the one with the single engine inboard, painted on a six-foot canvas with some local background to hang in my office.”

Therein exists the difference between my patrons and those gallery clients who peruse the walls of exclusive spaces buying from an array of artists who create in their own vacuum. Gallery clients buy for whatever mysterious reasons. Is it the signature? Is it the style? Is it the frame? Is it an investment? Are they getting what they really want hanging on their wall? Do they even KNOW what they want hanging on their wall? Is the painting really speaking to them? Who knows?

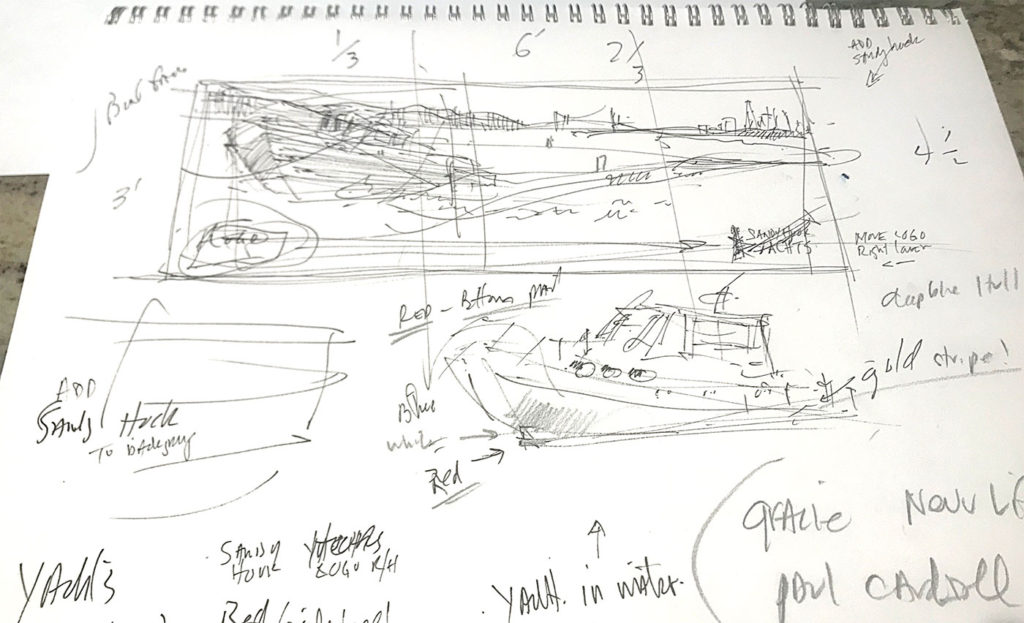

Subject matter is always inspirational. Dan and I decided where that boat in his envisioned painting would appear, and in what direction it would be headed. Soon I was planning the broad scope of his basic idea. All that remained was to lay out a visual description, make changes and additions, and get his approval. Out comes the sketchbook.

I suggested, “How about we put the boat on Sandy Hook Bay covering the left third of the painting. That way I can get Staten Island as a backdrop with a clear view of the Verrazano Bridge in the distance, along with the New York City skyline. I can get Fort Hancock in there, the Coast Guard station and show Officers Row on the far-right side.”

While I describe what I’m thinking I draw out the rough on a sketch pad. Dan agrees, disagrees, makes changes but there aren’t many. Seeing someone’s vision eliminates wondering how they’ll like the finished work later. His only request: put his logo on the right-side lower corner. The meeting lasted 15 minutes.

Now my work begins. Throughout the whole process “Back Cove 41,” the boat Dan requires, is a research piece. I draw, photograph, study, and look up everything about it inside and out. The wake it throws has to be right. Two small motors deliver a different wake than one big engine. The boat sits on a different angle in the water at full throttle. I’m a decent detail-man and I give it my best research efforts.

From first brush stroke to last: it’s all about the boat.

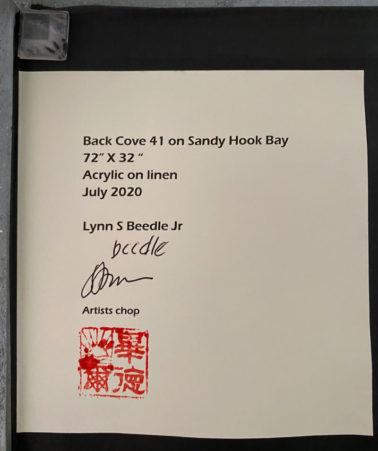

For many reasons, such as cheap materials and low quality of the commercial canvases out there, I find it necessary to construct my own. I built the frame out of 1×2 clear pine, 72 by 32 inches — shaved, nailed and glued so it would never warp. Onto that I stretched linen instead of the usual duck and primed it front and back with coats of gesso: one fine, tight, indestructible end result for a painting surface. I waited for the best sky, took it outside, stood the canvas chest high on my studio easel and painted the atmosphere over an, as yet, imaginary calm Sandy Hook Bay.

Here is where all the intangibles come into play that makes the painting what it is in style, color and light. The boat is going full speed. But still it’s coming towards you on this obtuse angle. Its 6PM on a summers day and the western sun is starting to catch the scene with evening light. The lines are correct, the foam is lit. A Captain at the helm is in control, blasting across our view revealing his vessel’s bow, windscreen, interior, hull, fantail and a wake now lit by shadow and sunlight. The whole scene is moving, yet the gateway and skyline across the water stand stoically — waiting for a turn starboard towards the Ambrose Channel and the world’s shipping traffic.

These were my thoughts as I put together the painting “Back Cove 41 on Sandy Hook Bay.” This beauty took a while. It has much underpainting, but the best result is on the surface. I tacked on a “ship-lap” type white frame, backed and wired it and made the call. With a delivery early in the morning Dan admitted to me he had no idea what to expect. He was all smiles. Like many of these kinds of paintings, often they turn out to be exactly what they had hoped for. Dan was jazzed. He took one look and decided the best location wasn’t his office at all but the lobby where everyone could see it. This was a successful commission delivered to a happy patron.